Editors’ Note: Katherine Arnold and Eriks Bredovskis convened the seminar Colonialism and German Memory Politics: New Approaches to Teaching Colonial Science and German Imperialism at the 2022 German Studies Association annual conference. Because the seminar focused on teaching, the Collaboratory editors asked the conveners to write a recap of the seminar for Zeitnah.

Recently, the legacies of Germany’s colonial empire are featured more regularly on the front pages of German newspapers and in the foyers of brand-new museums like the controversial Humboldt Forum. While German historians and Germanists have been writing about Germany’s colonial empire, its legacies, and memories for years, these discussions usually remained within the academic sphere. With growing public—and student—interest in the legacies of European colonialism, we felt that there was enough interest to organize a seminar on the research and teaching of German colonialism.

Our seminar (titled, “Colonialism and German Memory Politics: New Approaches to Teaching Colonial Science and German Imperialism”) initially had two goals. First, we sought to interrogate the roles of histories of science and colonialism in German history and German Studies. We felt that ‘science’ as a subject was as productive for the future as it is for historians studying the past, a crossroads allowing us to engage with questions on contemporary issues in Germany relating to race, museum collections, linguistics, medicine, universities, etc. Second, we wanted to carve out time at the GSA to think about our teaching of these subjects. Has the teaching of German colonialism evolved in step or at odds with research on the subject? We felt that a seminar that discusses the research and how we, as educators, share that knowledge with students and the broader public would yield dividends.

As we crafted our seminar proposal, contacted prospective participants, and reflected on the current state of the field, a third and fourth goal materialized: to strengthen the vibrant network of younger scholars of the GSA who completed their PhDs in the 2010s and early 2020s, and to bridge the divide at the GSA between history and Germanistik.

When designing the seminar, we did not want it to be just another seminar where participants circulate draft manuscripts that orbit one topic. We wanted to know more about the spaces in which we work: university classrooms. Discussing pedagogy seemed obvious. The COVID-19 pandemic and the initially rapid switch to online teaching, then (for some institutions) swinging to in-person, then to hybrid, and then to online teaching, forced many educators to reflect on pedagogy in higher education. How does one teach history or language acquisition (and assess students) to a wall of blank screens?

We asked participants to produce two written pieces before the seminar. The first was a group-written 500-word piece that answered the question: If you could write a syllabus on colonial science and German imperialism, how might you approach it? The second piece was a three-page solo-written reflection about their pedagogical approach or the state of their respective field. These two pieces introduced participants to each other before they arrived in Houston and let them know that our seminar would be more self-reflective than the regular GSA seminar.

On the first day, we talked about how we came to the seminar and the state of our fields. We were lucky that our seminar participants came from different universities, countries, stages in their careers (from fresh Ph.D. candidates to tenured professors) and from Germanistik and German history.

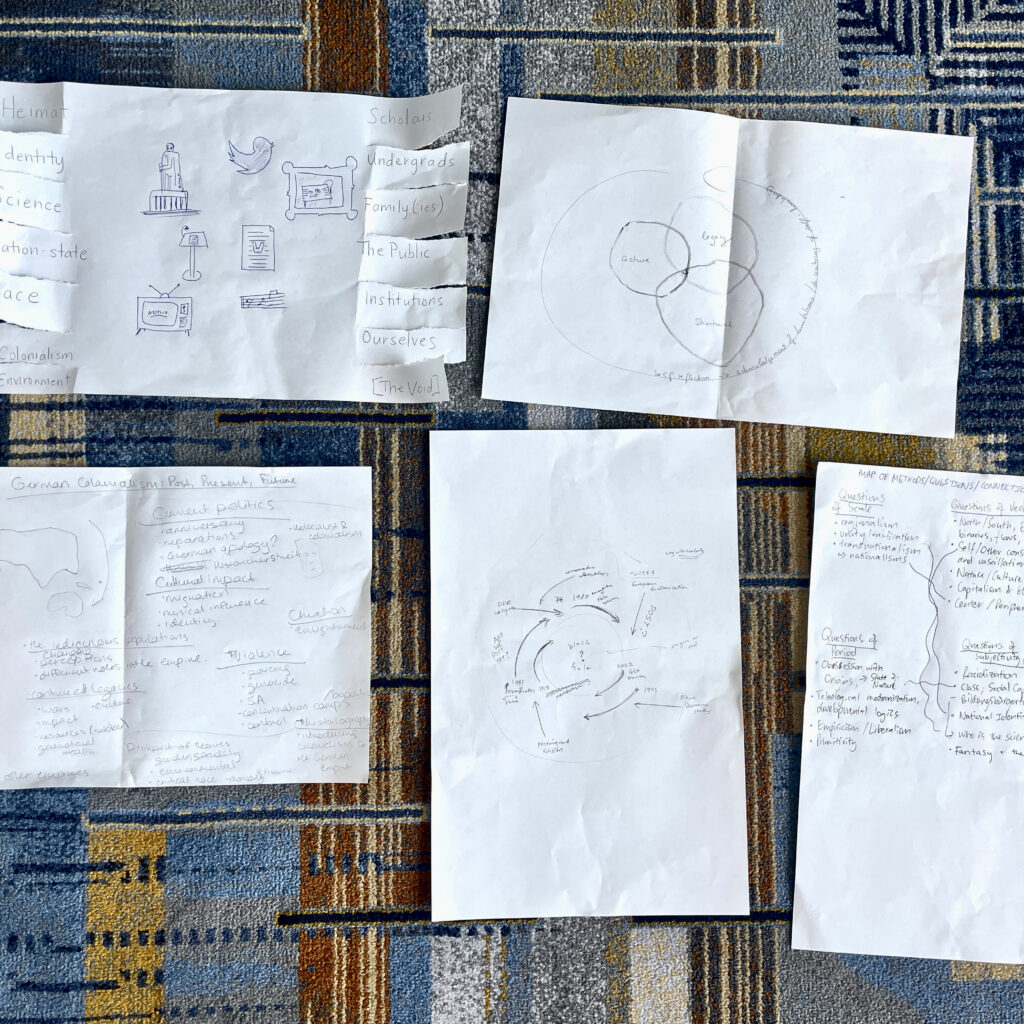

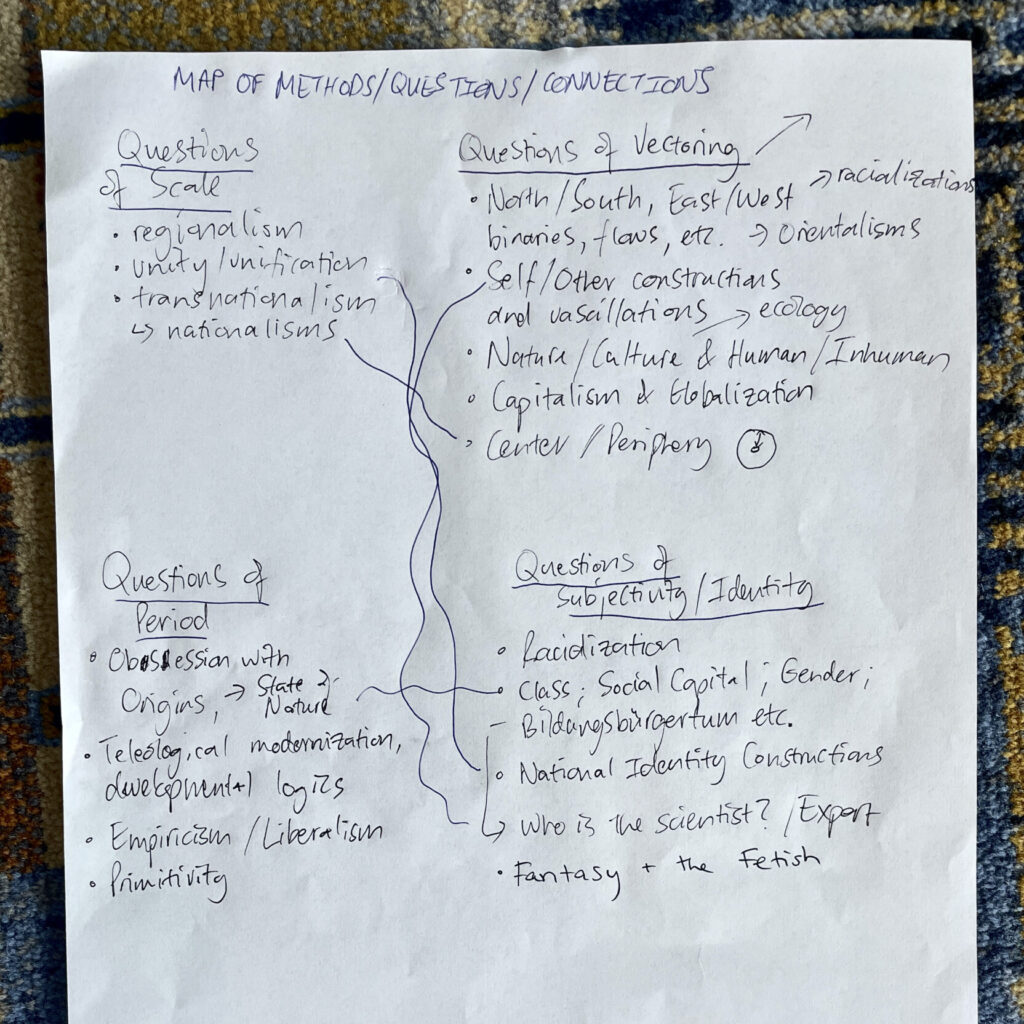

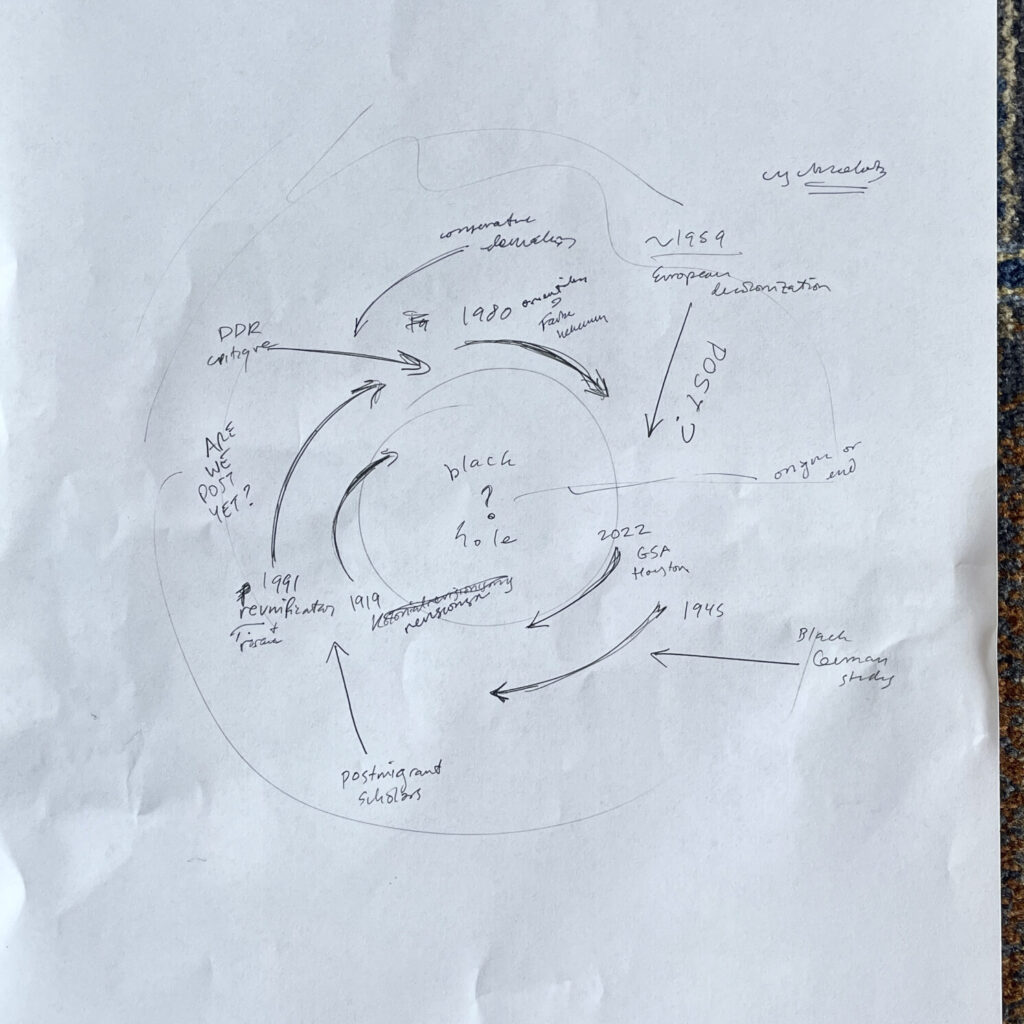

We talked about what made us apply to the seminar, and then in groups, we started our first creative exercise. With a sheet of A3 paper, each trio had time to sketch the field, literally, with paper and pencil (see the slideshow below). Then we grouped and shared what we found. Seminar participants saw the current state of the field differently, but all imagined a better discipline, university, or department—not only for us but also for our students.

We returned to our seminar room on day two, knowing that the field needed to change, but what was preventing us (as educators) from fulfilling our goals? What are the challenges in creating our ideal German Studies or history program?

We took an exercise out of Minieri and Getsos’ Tools for Radical Democracy (2007) called Power Mapping. Power Mapping identifies issues and decision-makers (the individual who can solve our issue) to focus our efforts and build power toward attaining our goal. For example, one problem we identified was that there was no space for discussion of German colonialism and colonial language in German language courses. The solution to the problem is to dedicate some time in the classroom to talk, possibly in English, about Germany’s colonial legacy and how it relates to contemporary notions of Germanness. The decision maker, in this case, would be the department chair or the language program director (depending on the university’s structure). While some tenured faculty could adjust their syllabus, this would not change the structures which created the issue, nor would it be a long-term solution (furthermore, some departments have a carefully designed curriculum, and most non-tenured faculty or contract educators don’t have control over their syllabus).

We charted about a dozen issues and decision-makers. We learned what issues each of us have in creating a more equitable and just classroom and how each department and university organizes itself differently. Most importantly, we were becoming aware of the structural contexts of our teaching and how to improve teaching beyond our classrooms.

Participants crafted the kernels of a syllabus between the second and third day, focusing on one themed week. Then participants shared their syllabi, and we concluded with an open discussion on how our seminar went and the next steps—what do we need to do next to continue this move?

We are glad about how our seminar turned out. Focusing on pedagogy from the perspective of teaching German colonialism created new spaces for members of the GSA to talk about their own experiences in pedagogy and the challenges of teaching at post-secondary institutions.

The next steps are always a challenge. Organizing and running a seminar was a wonderful experience, but what do we do now? Within the GSA, this would mean establishing a dialogue and partnership with existing GSA interdisciplinary networks such as the Asian-German Studies, Black and Diaspora Studies, Digital Humanities, and Teaching networks. This academic year was, for most institutions, the first “full return to normal”: we faced administrative pressures to perform “like before,” rising precarity of contract faculty, and more have all contributed to many of us reverting to easier ways—easier is not always better. We hope that participants (and us as the organizers) see that a better and more just way of teaching German history and Germanistik is possible and that there is a group of like-minded GSA members who want to make higher education a better place.

Katherine Arnold, University of Liverpool

Eriks Bredovskis, University of Toronto